“Aubade”

7:01: the first rain of the last day

of August starts to fall, then hesitates,

postpones itself to let the light

that would have come here anyway break in.

Nothing is amazed. None of the azaleas

have changed their minds about not blossoming,

and the lady cardinal who visits the lawn chairs

between 7:15 and 7:20 assumes her station

and finds the yard in its ordinary order.

But she must notice how the long branches

Of the euonymous, yesterday so straight,

Now are bending under days of dryness;

how the fig tree’s leaves are browning,

as if burned by a slow, exhausting fire

the small rain did not extinguish. Summer’s

steady certainties, the creeping

increments of heat and leaf, falter

and break, utter final colors.

No expectations could sustain these last

intact yet stunted primroses. After all,

what is the soul? The black ant

mazing through the rose’s sex?

These tendrils shrinking from the endings of air?

The repetitions of cloud and sky,

the kinetic clocking down of things

caught in the cardinal’s eye in flight?

— from Habitations

by Brad Richard

Brad Richard, New Orleans poet, writes with an incredible sense of perspective and place, reaching out toward history, mythology, art, and nature. Focus and attention are revealed in his poems, as well as questions regarding gender, an understanding of the world, literary and otherwise, and a way in which to examine it. Though I’ve known Brad for years, I’ve learned so much more in this interview about his way of seeing and about the form and fabric of his poetry.

Backyard Ferns

Confederate Jasmine

Brad, I’m thinking about the idea of perspective in your poetry. In your first collection, Habitations, many of the poems focus in on nature, as in “Aubade” and “Dirt-Dauber’s Nest,” and then lean away to widen and expand. And then there are those pieces that steal in and single out details that perhaps we’ve no business knowing, like “Everybody’s Little Secrets.” I felt a terrible, wonderful sense of voyeurism here, the digging down into places that are usually off-limits, and realized that these sorts of poems have a literary kinship with Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio and William Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying.

Would you speak about your process, in terms of perspective? And about how that process may have evolved over the years?

First of all, Karin, let me say thanks for this interview. I’m really honored to be one of your subjects.

To the question at hand: I love looking at things and I love describing them. I hope my eye doesn’t censor what it sees, that whatever is seen is fair game for thinking, feeling, writing. Still, at times I feel incredibly obtuse, like I miss things that are right in front of me. Then again, I’m always surprised when someone reads one of my poems and something I’ve seen, something I may have thought was so obvious as to be banal, strikes a reader as perceptive. I think it’s just the habit of looking that makes me notice things in a particular way—something particularly beautiful, or odd, or telling.

Imagination is the next step, and that involves a looking out as much as a looking in. That is, if I can imagine myself into something (a person, an object, a painting), I hope that I can see from that particular perspective and generate some sense, however partial, of how that consciousness would think. I’ve written a lot of persona poems and dramatic monologues and variations thereon, and that mimetic habit of imagining a different perspective runs closely parallel, I think, to the habit of seeing I described above. What interests me the more I write is how I locate whatever I consider to be my perspective.

I love Sherwood Anderson (“Death in the Woods” is one of the most brilliant and haunting things I know) and As I Lay Dying is a touchstone. And yes, the sense of being a little too close for comfort is something I admire and am a little frightened of in Anderson and Faulkner’s best work.

Fiction

Poetry

You’ve written poems as tributes to other poets and to artists, landscape, mother, father, lover, self. And that’s all very nice. But here’s my question: have you ever written a poem of thoughtful, quiet revenge? And (even if you haven’t) what, pray tell, is the best poetic form for writing of reprisal?

I love this! “Writing well is the best revenge,” said a writer with a famously poison pen. And George Garrett perhaps wrote the wickedest bit of literary revenge in his novel, Poison Pen (dedicated to the memory of Joan Rivers). I can think of lots of examples of well-turned vengeful daggers in prose, but I think what makes literary revenge work is the same in poetry. It’s a matter of finding the appropriate balance of irony, ire, and bile, and singing your hate-song in perfect, pissed-off pitch.

Now, in my own work . . . hmm, is there anything I would admit to as arising from wanting to settle a score? I’ll take a kind of middle road with the two poems I’ll cite. One is “Eye-Fucking,” from Butcher’s Sugar, which is in the persona of a gay-bashing murderer. Letting him speak for himself is, to my mind, pretty good revenge. The other is “The Artist’s Wife and Setter Dog,” from Motion Studies, in which I play a trick with point of view, withholding the identity of the speaker for as long as I can until it’s clear that it’s the wife, that is, Mrs. Thomas Eakins. He and she had a very complicated relationship, but I felt she deserved a chance to speak her mind about how that horrific portrait portrays her. Withholding and then revealing the speaker was a way both to complicate and dramatize how Eakins repressed her and her image. I hope a little brute justice was served in that case.

Now, if you were hoping I would reveal some juicier, more personal poetic revenge . . . sorry!

Poetic devices

Place informs so much of your writing. Your childhood in Texas, your adult life in Louisiana, the interim in Iowa and Missouri. Armadillos, levees, gulf waters, wasps, acorns, mockingbirds, sweet potatoes, wild sweet-peas, locusts: details of those places.

Within place in your writing are intonations of desire—to be home; to be elsewhere, near the shore, examining things washed up; to be wanted, loved, understood. What do you think? Places, people, passion. Sound familiar?

Of course. A person who will remain nameless (note to self: subject for revenge poem?) once made fun of me when I told him I was considering learning more about birds so I could identify them more precisely. Clarity is my absolute standard for good writing, and precision is fundamental to clarity. This is all essential to understanding place in a meaningful way. Places, people, passion: these things are very specific, and it’s their specificity that moves me.

Motion Studies - by Brad Richard

“Motion Studies”

I. [1929 / 2005]

We’ll never make it in time: you’re twelve,

Riding west to see a corpse in a flood,

I’m your grandson at forty-two, riding east

to see my city’s flooded remains.

Gueydan to Port Arthur, Austin to New Orleans,

you in a pickup with your daddy and one brother,

another brother waiting in a funeral home,

laid out in somebody’s suit on a cooling board,

you trying to imagine that body past this rain,

me in a rental car with the music cranked,

trying not to think about stories that got snagged

in stories that failed to hold up, to hold

water—

— from Motion Studies by Brad Richard

Motion Studies, the title of your second collection and of three movements within the collection, becomes the telling of stories within stories, like sketch boxes inside the set of suitcases that, from smallest to largest, fill the old leather trunk in the biggest closet of your father’s art studio.

Would you tell us about the circumstances surrounding the writing of these poems? How they came to you, from the art examined to the exodus from and the eventual return to New Orleans?

I love how you imagine this big leather trunk in my dad’s studio! There wasn’t one, but you’re absolutely on target with the metaphor of stories packed into stories. And I’m delighted to talk about this.

I began writing the Eakins material in Motion Studies in 2003, after seeing the Eakins retrospective at the Met in 2002. I really didn’t know his work before then, and was in the middle of working on the poems that would find their way into Butcher’s Sugar. But Eakins work really got to me: I admired it, I was annoyed by it, and I wanted to make it give me something back for all the energy I was putting into looking at it, especially that damned Swimming painting. I ended up doing a considerable amount of reading and research and was planning to write a book of poems almost entirely about Swimming. By the summer of 2005, I was pretty far along with that project, and well into its explorations of impossible yearning. And then that stupid storm happened.

Among the many ways that Katrina affected me, one of the worst was it (or my reaction to it) made it impossible for me to continue the Swimming poems. Fortunately, I had already written a lot of those poems, and probably even more fortunately, they weren’t just about that painting. While Tim and I were in Austin, during our weird, extended evacuation period (our apartment was fine, the city wasn’t, and we didn’t need to return immediately), the Ragdale Foundation graciously offered me a residency. I went there to write one poem, “The Raft of the Medusa,” based on the very famous and much-written-about Géricault painting; that poem ended up taking months to finish, and I really meant for it to be my only Katrina poem.

In the summer of 2008, I received another Ragdale residency; I hadn’t been writing much during the previous year, and I was frankly unsure what to work on. I knew I didn’t have enough Eakins material for a book, but I also knew that work was good enough to become part of a book. I was also wondering if I could find a way to write again about Katrina that would mean something to me, just as the writing of “The Raft of the Medusa” had: not something merely didactic, but something really felt. About a week before I left, I had one of the few “eureka!” moments I’ve ever experienced as a writer. I suddenly realized that my Katrina story, a story about my paternal grandfather trying to get to Texas during a 1920’s flood to retrieve the body of a dead brother, and Zeno’s paradox were all related and could generate a single poem. It took a lot of work, including genealogical research, research about cooling boards (thanks, Audrey Niffenegger!), and imaginative re-creation, but over that four-week residency, I came up with most of what become the “Motion Studies” series that forms the spine and nervous system of that book. I’m still amazed that all of that meshed so well with the Eakins material, plus a few other poems I had written previously. I don’t expect to ever again have such an incredible experience of unity in creating a book.

Freddy’s tail

Butter Boy!

Influences: literary, cultural, culinary, gender-wise, otherwise.

I always go a little stupid when I have to answer the literary influence question. Once I start listing the usual suspects (Bishop, Stevens, Yeats), I feel obligated to start listing everyone whose work I love and has had some impact or left a trace on my own work and then I freeze up, can’t think, babble. So I’ll try this.

Literary: Gilgamesh. Moby-Dick. King Lear. Yeats, Stevens, Bishop, Plath. Tomas Tranströmer. Michael Alexander’s introduction to The Earliest English Poems (Penguin, 1966). Andrew Marvell’s “The Garden.”

Partially literary/extra-literary/cultural/etc.: I have and have had many important literary friendships, and Dana Sonnenschein and Reginald Shepherd have been the most important of those. Dana’s friendship sustains me in all kinds of ways, and Reginald’s changed me, big time. I’m in a talented and invaluable workshop group—Peter Cooley, Melissa Dickey, Carolyn Hembree, Andy Stallings, Andy Young (and past members Jessica Henricksen, Major Jackson, Ed Skoog, Liz Thomas)—and am lucky to live in a city with a vibrant, diverse literary community. My relationship with my father is where my relationships to the visual arts, music, and food begin. Gender-wise = otherwise. OK, that’s a joke. Sort of.

Gladys – former bridesmaid, always the hen

Crawfish: étouffée, bisque, or boil? And how come?

I have to choose?! Well, boiled is the most fun, so I’ll go with that.

Butcher’s Sugar by Brad Richard

“The Men in the Dark”

Dropping shut the trapdoor that opened the dark

above my childhood bed, they don’t want me

to tell you about them, those two men

who left their smell with me each night

until I was no longer a boy. In tee shirts

or sometimes shirtless, they sat on bunks

as in a cell, smoking cigarettes and staring

down as I whispered. They liked to hear

about my parents, my dog, hurricanes, the wasp

and the dandelion, how blood tastes, how deaf people talk.

– from Butcher’s Sugar by Brad Richard

In your third collection, Butcher’s Sugar, you step out onto the ledge of gender, curling your toes toward “dirty boy” poetry, then lean over the edge toward yearning, sex, and even homophobic violence.

Tell us more. What else were you moving toward with these poems? And have these pieces led you into another dimension in your writing, a place where you can take off into the next stretch of work?

The first poems I wrote that ended up becoming part of Butcher’s Sugar were exercises in form: “Queer Studies” came from practicing the sonnet, “The House that Jack Built” from practicing the villanelle. I wrote sonnets and villanelles on other subjects, but in these particular poems I was interested in queering the forms. I didn’t think they would necessarily lead anywhere; they were exercises. I did play around with similar material, most of it also in forms, but a lot of it was pretty bad; this was back in the mid to late ‘90s, when the manuscript for Habitations, my first book, was basically done, and I was looking around for a new direction. I really didn’t know what I wanted to do and a lot of the abandoned work from then reflects that.

There were two turning points. One was “Eye-Fucking,” which was a response to reading about gay-bashing killers in Texas. Although I had played around with writing about creepy material, that was a more visceral writing experience, one that made me confront the real horror of what I was dealing with, and made me question why I wanted to write about it. After that, I couldn’t deal with material of that gravity without feeling more certain that it was OK—morally and artistically—for me to do so.

The other, more liberating one was a re-encounter with ancient literature, specifically Gilgamesh and Greek mythology. That gave me a frame of reference for dealing with material that was quite personal, even in poems that don’t refer directly to classical myths. I’m not a Jungian, but archetypal material is undeniably powerful, deeply referential in ways that heighten the intensity of a poem and give them a certain density (which I hope isn’t merely borrowed). I feel that, too, in the kind of material I drew upon for Motion Studies.

Motion Studies is a very elegiac book with some hope for the living, for those who can remember, for the lovers at the end. Butcher’s Sugar is also elegiac, but brutal: of all the classical influences in it, the strongest may really be Euripides’ The Bacchae, which is, in my reading, about the question of whether it’s necessary to destroy the self in order to have self-knowledge.

Right now, I find myself working between two impulses. One is directed outward, toward the idea of the city and of history, in a partially completed manuscript about the capitol of an imaginary kingdom and in another about New Orleans (which is also kind of an imaginary capitol). The other impulse goes more inward, and a lot of that material is very domestic; there are poems about things growing in my yard, and about my life with my husband, Tim. (Not coincidentally, I’ve been going back more often to James Schuyler’s beautiful poems.) Related to these are some memory poems, some cousins to poems in Butcher’s Sugar, others more like poems from Habitations. Which means, I guess, that I keep coming back to place and perspective, trying to get my bearings again and again.

Reprise of Freddy’s tail

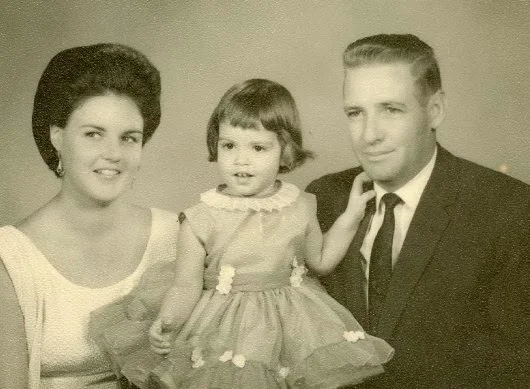

Tim Watson & Brad Richard – Hansen’s Sno-Bliz – New Orleans

Brad Richard

Brad Richard is the author of Motion Studies (The Word Works, 2011), Butcher’s Sugar (Sibling Rivalry Press, 2012), and Habitations (Portals Press, 2000). He chairs the creative writing program at Lusher Charter School in New Orleans.

All photos – with permission of Brad Richard and Karin C. Davidson.

*

The Poppy: An Interview Series

Four to six questions begin as pods, then burst open with answers, bright lapis,

black-stamened, conspicuous—ornament, remembrance, opiate.

*

This interview first posted at Hothouse Magazine.