“Out the window, the tide is changing, the sea frothing and roiling into the tight channel. But beyond, in the harbor, it expands in relieved swells, glad to be past the slick mountain walls. Four months ago, Laura had gone to see Dr. Harnaysingh. She’d made an appointment because at forty-six, her body was suddenly an unknown entity. Once calm and predictable, a source of surety and absolutes, it was now dense, fleshy, prone to thickened skin and odd middle-aged lust… pregnancy was not something she’d considered… When she’d told Mark, he’d lifted her nightie, rested his dark head between her ribs and hipbones, and traced gentle circles around the hard space above her pubic bone. She’d imagined a light swooping and fluttering deep inside of her as Mark murmured to the quicksilver heartbeat, that mere conspiracy of cells. A baby.”

– from “The Whale House”

by Sharon Millar

2013 Commonwealth Short Story Prize co-winner

Sharon Millar – Photo credit: Mark Lyndersay / lyndersaydigital.com

Sharon Millar, a Trinidadian writer, shares her insights about writing in terms of language, landscape, cultural identity, and literary influences. Her lyrical stories are informed by the Caribbean and address issues central to life there. For instance, how life repeats itself in traditions and behaviors laden with love, sexuality, and violence. That we shared a writing mentor—Wayne Brown, the late Trinidadian writer who wrote from his home in Kingston, Jamaica—is an honor. Wayne had high expectations, which Sharon fulfills in her writing, her prose remarkable in its risk-taking, compelling narrative voice, and lush language.

Trumpet flower

Forest foliage

The language of your writing is rich and detailed and saturated in landscape and sense of place. Would you speak about the Caribbean, as well as your inspiration and your process?

It’s interesting to try and see where inspiration comes from. How do we choose to tell the stories that we do? It’s taken me a long time to pin down my process.

I’ve been writing seriously since 2009. I’d always dabbled before, but it was only when I began writing with Wayne Brown again (I’d done workshops with him in the early 1990s) that I began to really write. Sadly, I kept almost none of this early work. This was before the days of the internet, and to take part in his class I had to rent a typewriter. That’s one of my biggest regrets. I’d love to look at the work now.

I write from landscape, which is to say I often have no idea what I want to write. Random things are triggers. Right now it is July in Trinidad. We have moved from dry season to rainy season. It’s almost like a different island. The light changes, the humidity in the air increases, little ferns appear on telephone poles.

Trinidad's tropical waters

All of these are subtle cues. I tend to latch onto a feeling in the air or a certain heaviness of the light through the humidity and this will propel me in a certain direction.

The Caribbean islands have complicated histories of oppression and violence. Like the American South, slavery is an inescapable and tragic blot on the region. We are a young country. Just barely 50 years old with a very multi-ethnic population. Daily the population struggles with issues of identity and belonging. That’s the negative side. The positive side is that there are so many stories to be told. I really believe in the power of the story to help us see ourselves.

My biggest challenge is to write against all the stereotypes of the Caribbean. The rest of the world sees the Caribbean region as having one culture, one people, one collective history. I think it’s up to the fiction writers to show the world that each island is different and that we are much more than the tropical stereotype.

I’ve been told that I write in a very specific manner. I do this deliberately because I want the reader to see and hear and taste and smell what it is I am trying to convey. So I pay close attention to the small things. The plate of food on the table, the way the chair feels under the protagonist. What’s gratifying is when people say – oh, I felt this story had to be addressed to me because only I could feel this way – that’s very rewarding. I think that the specificity enables the work to be both very personal and very global.

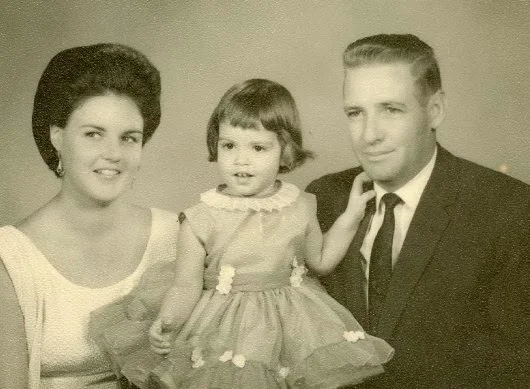

Sharon and her parents

Family relationships, including the passing of happiness as well as grief from generation to generation, are prevalent in your writing. Would you share a bit about your family and your background?

We are white Creole and have lived here for as long as my family can remember. My mother’s paternal family goes back to the 1600’s (out of Barbados), her maternal family are more recent, coming to Trinidad in the mid-1800’s from Lisbon. On my father’s side, it’s a mix of English and French. The white Creole narrative in the Caribbean is one that is difficult to reconcile with my day-to-day life. But I am moving slowly towards mining the stories, both the good and the bad. And there are so many stories.

Sharon as a young child

Sharon and her sister Jennifer

My younger sister and only sibling, Jennifer, lives in Miami. She is about five years younger than I am. We had a good childhood with many pets, vacations near the sea, friends.

Sharon's mother as a child

But there were defining tragedies that shaped us.

When my grandfather was in his early sixties, he died suddenly. He had a heart attack in his study and died at his desk. It was the day after my birthday. I had just turned five, and my sister was only nine months old. My grandfather was an independent senator, and so his picture was posted on the front page of the newspaper. I remember my mother crying. She was an only child and very close to him, so this was a loss from which she never fully recovered.

At 54, my mother was diagnosed with breast cancer and succumbed to the disease ten years later. Her death is the hardest thing I’ve faced. And, Karin, you have put it so eloquently – the passing of grief from generation to generation. And it’s strange that I’ve honed in on this area of my life. I feel as if I’m the keeper of all the stories now.

Sharon and her daughter Hayley

I’m married with one daughter. I’ve been lucky in many ways, but no one escapes grief.

Dusk at the Waterloo Temple cremation site

Literary influences?

I am influenced by what I read. I went to university in Canada and read lots of early Margaret Atwood, Margaret Lawrence, Alice Munro. Also Doris Lessing, Nadine Gordimer, and I love Bessie Head and Ben Okri. I always liked reading the women. I loved Russian literature for the sheer magnitude of the landscape. I don’t consider myself a feminist because the very label carries its own level of patriarchy, but the women appear in my writing. I’m still reading and learning the Caribbean canon, an intimidating and essential one. Sir Vidia Naipaul, Earl Lovelace, C. L. R. James, Sam Selvon, Derek Walcott, and too many others to list here, have set a very high bar. I recently heard Jamaican poet, Edward Baugh, read in Miami, along with Edwidge Danticat and Earl Lovelace. When you hear the work and it resonates so deeply, you think, okay, that’s it. These are the ties that bind; this is what we share. This is what it means to be Caribbean in 2013.

The Caribbean canon is young and is naturally, very politically charged with issues of ethnicity and identity. Migration and displacement are constant themes as are oppression, power, and authenticity. For a long time I couldn’t write because I couldn’t see how I could bring anything to the canon. I simply couldn’t find a voice within that context. Now that I am older, I can see my way in, which is empowering. I can only write the story I know.

Trinidadian writer Wayne Brown

There’s something about the Antillean landscape that infects our writers. I see it in the works of Derek Walcott, V.S. Naipaul, and Wayne Brown. There is a lushness that marks us all. I wonder if one hundred years from now if it will be obvious. The current generation has poets like Tanya Shirley, Kei Miller (Jamaica); Loretta Collins Klobah (Puerto Rico); Vladimir Lucien, Kendel Hippolyte (St. Lucia); Danielle Boodoo-Fortune, Vahni Capildeo, Andre Bagoo (Trinidad), Sonia Farmer (Bahamas), and many more that I haven’t had the opportunity to read. Even though I write fiction, I read poetry when I need an entry point and the texture of the words. Then I move to fiction to carry me along. I’m experimenting right now, and perhaps those most influencing my work are fiction writers, Alistair Macleod and Andrea Barrett. But that’s today.

White Witch Moth on a coconut tree

Blue-crowned Motmot - Tobago

You’ve been writing a story collection, and a few of the stories have won awards. Is there a project you look forward to working on once the collection is finished?

I want to move on to a novel. One of my short stories declared itself a novel very early in the process. I’m enjoying the research and also looking forward to discovering how the form is different to that of the short story.

Divali lights

Favorite line, and why you are drawn to it.

“Soon the harbor was a scatter of lanterns floating above the water, face level, shoulder level.” – from The Bird Artist by Howard Norman

I’ve read thousands of sentences since I read this line and I still remember how I felt when I encountered it. There was something about the idea of the lanterns floating above the water. By using the face and shoulder references, my mind made a leap and I imagined not just light floating disembodied, but also faces. It captured that odd ghostly mood with such a deft touch.

Trinidadian architectural detail

Novel, story, or vignette? And why?

Novel.

This was a hard choice. I very nearly chose short story. But the novel is a world to me, the short story a moment. While I have been transformed and charged and shocked by a short story, I still look to the novel to really remove me from my reality. The world building in the best novels leave you homesick for worlds that only exist on the page. That’s magic.

Caribbean bloom

Caribbean breakfast

Best breakfast ever!

A big slice of fresh avocado and buljol (salted fish, lime, onions, olive oil, and tomatoes mixed together).

Sharon Millar - Photo credit: Michele Jorsling

Sharon Millar is a graduate of the Lesley University MFA program and is a past student of fellow Trinidadian writer, the late Wayne Brown. She is the winner of the Small Axe 2012 short fiction competition and the co-winner of the 2013 Commonwealth Short Story Prize. Prior to this, her work has appeared on several shortlists. She has been published in a wide range of Caribbean publications as well as Granta Online. Her fiction is strongly rooted in landscape and she draws her stories from both place and history. Cemeteries, the rain forest, and old buildings are all sources of inspiration. She lives in Port of Spain, Trinidad with her husband and daughter.

To read Sharon’s stories, “The Whale House” and “Earl Grey,” follow these links:

”The Whale House” - at Granta – “New Writing”

”Earl Grey” - at ArtzPub – Issue 20

*

Color artist photo – with permission of Mark Lyndersay.

Black-&-white artist photo – with permission of Sharon Millar – Photo credit: Michele Jorsling

All other photos – with permission of Sharon Millar

*

The Poppy: An Interview Series

Four to six questions begin as pods, then burst open with answers, bright lapis,

black-stamened, conspicuous—ornament, remembrance, opiate.

*

This interview first posted at Hothouse Magazine.